Anirudh Bhati

During the course of my research centered on the historical relationship between Cambodia and India, I came across a remarkable piece of authorship by Dr David Kenneth Bassett (1931-1989), a Welsh academic, who has written extensively not only on the British East India Company's presence in India, but also revealed intriguing details of much less scrutinized features of the Company's inner-deliberations and operations in the East Indies. The account presented in this paper also brings to light fascinating aspects of the political, economic and legal environment in the 1650s. At Mekong Research, we firmly believe in the importance of the expansion of free trade for the development of Cambodia and the region. We believe that while significant strides towards openness have been made in the course of recent years, a historical examination of the culture and customs as recounted by the officials of the British East India Company, may give rise to new ways of regarding the prevailing conditions.

I have highlighted some excerpts of particular interest from this paper entitled: "the Trade of the English East India Company in Cambodia, 1651-1656", the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, No 1/2 (Apr. 1962), pp. 35-61, Cambridge University Press.

By the middle of 1640s, a severe depression had taken over markets on the western coast of India, and the Surat Presidency began to press the directors of the Company to investigate trade prospects with parts of East Indies which had not yet been explored. As a result in 1647, the Company began to look towards Pegu, Perak and Johore:

These new enterprises were not blessed with much success. Competition from Gujerati and Malay merchants in Johore was so severe that no agent of the English Company was sent there again until 1669; from Acheh its factory was withdrawn for ten years in 1649. In Pegu, the factory at Syriam struggled on until 1657 largely because of the obstinacy of one of its staff. The dismal outcome of these ventures could not be foreseen in 1648, and it was in January, 1648, that the President at Surat, Thomas Breton, proposed sending an English ship to Cambodia. After his desire to find lucrative employment for the Company's vessels in "more remote parts, as Pegou and Johore", he added: "we also stand very well inclined to vissett Camboja and thos adjacent Cuntries, where in regard of their difference with ye Dutch*, goods are said to vend at extraordinary rates."

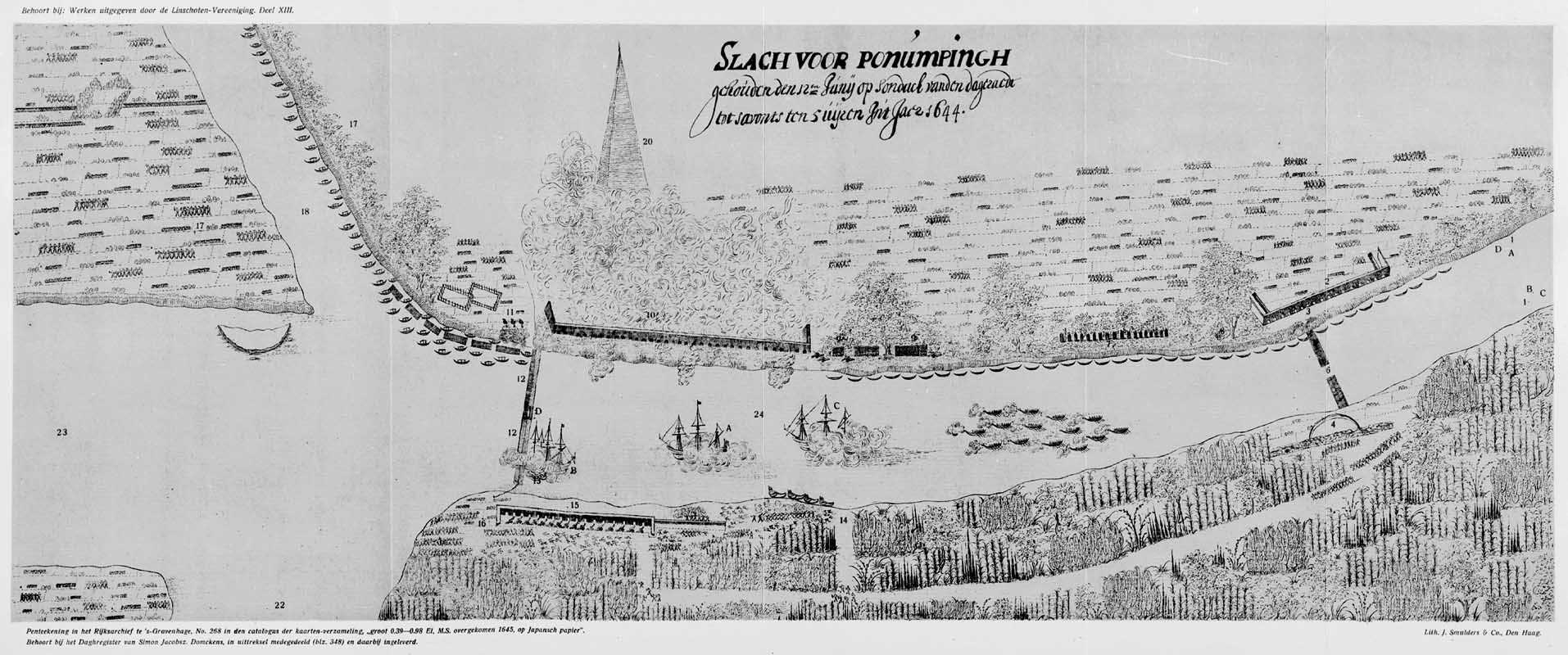

*The Dutch Company, abandoned its first factory in Cambodia in 1622, having reopened it in 1630. The Dutch chief factor, Picter de Regemortes, was murdered with his subordinates in 1643, and the Dutch retaliated by sailing up the Mekong to bombard Pnompenh in June 1644.

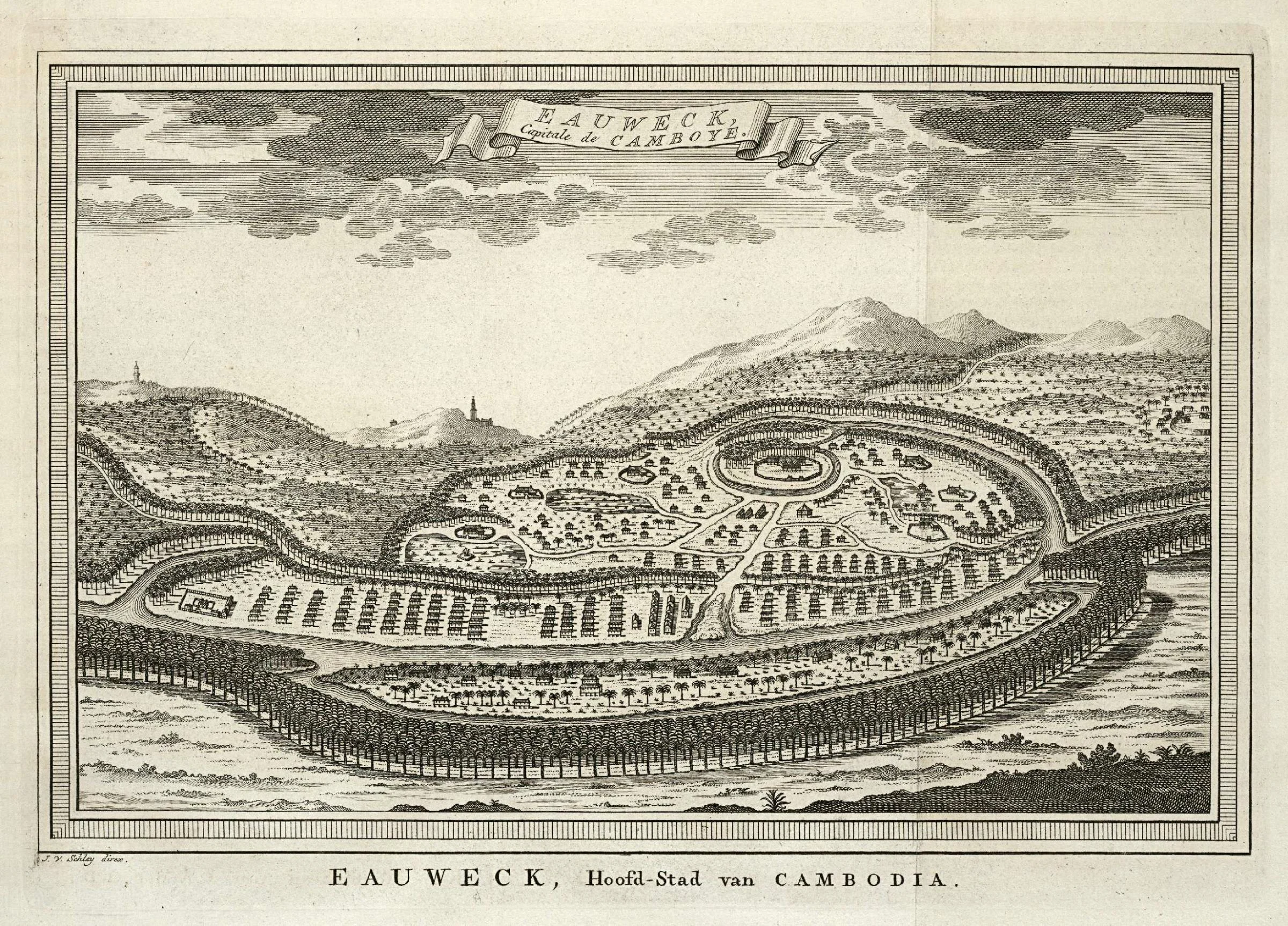

In the summer of 1651, a pinnace Francis was dispatched to Cambodia, to investigate the possibility of trade there. The chief factor for this voyage, Quarles Brown, related his experiences of his voyage to Longvek (លង្វែក, Lauweck, meaning 'intersection'), in an account of the Far East prepared for his employers. Dr Bassett added:

We have no contemporary evidence as to the activities of Browne and his subordinates in Lauweck in the latter half of 1652, but by piecing together various subsequent allusions it is possible to realize that conditions of trade were not as favourable as the English had anticipated. [...] The Chinese and the Malay merchants in Cambodia resented a new competitor in the market and Browne quickly discovered that free trade was a concept alien to the country's traditions. The king, Rama Thuppdey Chan (1642-59), was the chief merchant and he acted through his commercial agent, known to the English as "that disturber of Israell, Sudrea". Browne had his first taste of what to expect from Sudrea in 1652 when that gentleman "engrossed" most of the superior quality "head" and "belly" benzoin;* so that the benzoin sent was so inferior that Frederick Skinner, the agent at Bantam, stigmatized it as full of dirt, dust, and sticks, and only a little better than the type got second-hand through Macassar.

*Benzoin was usually graded at this time in descending order of quality into the "head", "belly" and "foot" varieties.

It was not until October 1654, that a peace treaty was signed between the English and the Dutch after the first Anglo-Dutch War. It fell upon Quarles Browne, the chief factor, to maintain a small settlement at Longvek.

In Cambodia, as in most other South-East Asian kingdoms in the seventeenth century there appear to have been certain basic methods of trade. The arrival of commodities in a port was governed by seasonal and monsoonal changes and much time might elapse between the sale of the Company's cloth and the appearance in the market of commodities suitable for the return cargo. So, there tended to emerge middlemen who held the cloth during the commercially dull months. Sometimes these middlemen could pay at once for the cloth delivered to them, when the transaction ended as far as the Company was concerned, the English chief factor retaining the money for investment in appropriate commodities at a later date. Usually, however, the Company had to advance at least part of the cloth on credit, the debtor to repay in a few months' time as he secured for the Company required goods from other visiting merchants. Accordingly, Browne signed an agreement with one "Noch(oda?) Ewes" in June, 1653, by which the Asian accepted specified type of Indian cloth at fixed prices and promised to supply the English factory in due course with clean benzoin at 15 taels per pikul. Browne's hopes must therefore have risen high when thirteen praus arrived from Laos in November with 1,500 pikul of benzoin, 700 pikul of sticklac, and some elephant's tusks but he quickly discovered that contracts were of little validity when opposed to the royal policy of monopoly. The king refused to permit the visitors from Laos to sell their wares freely and Browne could only bide his time in the hope that matters would improve.

Dr Bassett discusses Browne's interest in Cambodian timber:

With an eye to the future, Browne also informed agent Skinner [at Bantam] that he could buy planks and timber for ship-building in Cambodia to replace the supply which the English Company had obtained from Japara in Java before the abandonment of its factory there in 1652. Cambodian timber was reputedly of excellent quality, for according to the reports of the Spaniards, "ye wormes in 10 yeares will not enter itt," the only disadvantage being that the local custom was to hew out the centre of the tree, yielding two planks only from every tree, no matter how large. [...] If the Lauweck factory was supplied with enough slaves in the coming years, however, Browne was confident that the timber could be cut to English specifications.

By September, 1654, the English had another run in with the royals.

On 7th September, 1654, Henry Hogg was dispatched on a junk down river from Lauweck with cloth and money worth 1,219 reals to buy wax and elephant's tusks. On 13th September he arrived at "Chirsidoe, being the Chiefest and principall River of all ye Rivers of Comboia for ye yielding (of) Wax." The next day Hogg was informed that the local royal agent had received 3,000 taels from the king with orders to buy up all the wax in Chirsidoe. The English factor was forbidden to invest his stock until the royal quota, intended for the Batavian market, had been satisfied. Hogg also discovered that royal vessels had been sent to "Petrapon", "Semading", "Passack", and "Cherefling" for the same purpose. Not to be outdone, Hogg rowed a mile up river from Chirsidoe to investigate the market but was offered only a small quantity of wax at 18 taels per pikul. The royal agent was paying only 16 taels per pikul but the edict of the king forbidding trade was so strictly observed that the best Hogg could do was to contract with a Chinese merchant for 20-30 pikuls at 17 1/2 taels to be delivered after the royal boats had gone.

The 'severe competition' and 'excessive royal restrictions' present in Longvek were the chief reasons behind the English venturing outside the city, and this strengthened Browne's conviction that some 'energetic remedies' were necessary. Browne made some recommendations such as broadening the range of investments and the type of commodities the Company imported to Cambodia, and to "break out of the narrow confines of the market at Lauweck" in order to purchase products at reasonable rates.

At the same time, however, "our grand Enemie Sudrea" had made it difficult for the English Company to trade Indian cloth.

It was becoming increasingly obvious, too, that the English Company would have to abandon the idea of selling much Indian cloth in Lauweck. Sudrea, whose avowed object was to make all foreign trade pass through his hands, was as obstructive as possible and Browne declared, "this King with Sudreas Tradeing to Jaccatra (Batavia) brings for retournes such a quantity of Cloth that (it al)most Satisfies this Merkett." If the Company wanted to sell cloth, it would have to do it on the lines of the "inland trade" started by Hogg, but in a different area, for "w(ha)t Considerable quantity of Cloth wee put of(f) here is to Lowes (Laos) Merchants (after Sudrea and the King hath sould their pleasure)."

Dr Bassett's cites further examples of trade restrictions enacted for the benefit of the monarch and those close to him. In a letter annexed at the end of the paper, it can be seen that Quarles Brown had left a rather unflattering description of the sovereign:

He that was king of this place was an usurper & bastard to his uncle's brother, whom he killed with helpe of Moolans [Malays] & soe came to the crowne, which caused him from a pagan to become Muhumetan (for which murther & the cutting of Dutch [i.e. the murder of Pieter de Regemortes and the factors of the Dutch Company in 1643] God hath justly brought him to shame, for his vanquisher, the King of Cochin Chyna, putt him and his queen in an iron cage & shewed them through his countrey. His word was his law, yet [he] had severall [laws] written but tyed [himself] to none: he was accompted the justest kinge in those parts.*

If ever this countrey be again governed by Comboyans & the [East India] Company settle a ffactory there, the chiefe [factor] you send must be very carefull of offending kinge or greate ones near him, for they are very apt to take exceptions and therefor[e] a jurebas or interpreter is appoynted alwayes to speake to the kinge, although the partye who comes about busines[s] speakes his language. Then if any thinge that is spoken doth offend, the interpreter suffers for it; this hath bin the custome ever since the kinge killed the Dutch [in 1643], which was occasioned by their chiefe's rash and high language to him.

*It is difficult to determine which king Browne is referring at this point, but he had no acquaintance with the king of Cochin-China on which to base such a statement and therefore he must have had Rama Thuppdey Chan (1642-59) in mind.

On trade customs at the port of Longvek:

All nations that came to trade here; and their shabander was as a justice on all ordinary occasions & none can goe to speake with ye kinge unles[s] presented by him, who commonly acquaints the kinge what busines[s] they come about before they are admitted to his presence; if the busines[s] pleaseth him not, they may come often before [they] have audience. I found soe much corruption in our shawbunder that [I] was forced to procure of the kinge (by means of his queen) a protector, whom we repaired to when our shabander neglected our busines[s]; he was third to the kinge in power.*

The kinge receives noe custome but att arrivall of a shipp or shipps is presented with a considerable piscash [present], yet comonly att their returne he sends back to the president or agent [a present] in benjamin [benzoin], elephants teeth or elce neare to the vallue given. Besides him, the queens [sic] & great men have small presents, who never returnes any thinge in lieu, alsoe the shahbander, besides for every shipp he hath a duty called Addatt Capoll,** 65 tale [taels] on every shipp after her departure.

* The English factors would appear to have placed themselves under the protection [of the crown prince].

** Presumably a corruption of the Malay "adat kapal" - a law or regulation affecting shipping, but here used for a customs charge.

Browne's account of the natives is generally disparaging:

The nations are large & stronge for the generality, but dull & lazie, not like other people ingenious or desirous of riches, for onely necessity inforceth them to worke to clothe the bodye & fill the belly, but I suppose the custome of the countrey makes them soe careles[s], for the best of them are but the king's slaves & when they dye all but their chiefe wives are att the king's disposure. Nay, all strangers merchants for the tyme of their residing here are accompted the king's slaves. I shall proceed noe further with their custome[s], for I doubt these have bin too tedious.

On the trading communities:

The principall merchants here are Chinaes [Chinese] & Japanneses [Japanese]. Chinaes are a very deceitfull people & untill I had possession of what I had bought, it was a doubtfull bargain and before I delivered what they bought of me I had my bargain under their hands & witnesses to it. Then if they were not able to make satisfaccon, the law gave power to seize on slaves, wives & children, & if they would not satisfie, then they themselves & sell them, for there is noe plea against handwriting.

The Japannesaes [Japanese] are the noblest merchants in those parts, free from baffleing, constant in his [sic] bargaines and punctuall in his tymes for payments, a ffirme ffriend, but [on] the contrary [i.e. to the Chinese] irreconcilably just in his weights & measures.

In this citty merchants doe not live mixt, but Chinaes in a street by themselves, Japans, Moolans [Malays], Javas [Javanese], etc., each [has] their place apart; the two last of these are not to be trusted, except in petty matters.